The “Cursed River” of Chambal is a blessing for riverine wildlife

By Dr. Oishimaya Sen Nag

Dark, ominous clouds had gathered in the sky. A storm was brewing, and in front of me were the turbulent waters of the mighty Chambal River. A river with a history as dark as the clouds looming over it. This river’s deep and mysterious ravines were once the playgrounds of dangerous dacoit gangs whose merciless acts were known far and wide. Today, fortunately, this river is known for better things. It is one of the last remaining homes of the critically endangered gharial and the endangered Gangetic river dolphin, and of course, the mugger crocodiles and a host of other fascinating species. A large section of the river is also protected as part of the National Chambal Sanctuary. As I stood there with these thoughts on my mind, my guide advised me to return as a boat ride on this stormy day in a swollen river abounding with massive mugger crocodiles would not be a very wise act. That year the monsoons were particularly heavy, and the river was literally overflowing its banks.

The Chambal, however, is not easy to forget, and hence, I had to return. After my first encounter with the wild and raging river on a stormy day post-monsoon, I revisited the river on a clear winter day in January, and this time, the river greeted me in a completely new avatar. The river was inviting and thriving with life.

A tributary of the Yamuna, the Chambal begins its 960km long journey in the Vindhya Mountains of Madhya Pradesh, from where it flows into Rajasthan and onwards to Uttar Pradesh, where it joins the Yamuna River. While at one glance, the Chambal might look like any other river, nothing can be far from the truth. Its past is replete with dark stories. It is often called the ‘cursed river’ in mythology. It is said that once a king named Rantideva sacrificed thousands of animals to attain supreme power, and the blood of these animals gave rise to this river. Yet another story connects the river to the great epic of Mahabharata.

According to it, the Kauravas and the Pandavas played the decisive dice game on this river’s banks. When Draupadi was disgraced following the victory of the Kauravas, she cursed the river, which bore witness to her insult. She cursed that a feeling of extreme vengeance would consume anyone who drank the river’s water, but the person’s thirst for revenge would never be satisfied. While these are stories from the yore, in more recent years, the Chambal was associated with the infamous dacoits of Chambal, who ruled the badlands along the river’s banks and spelled terror in the area and beyond.

Interestingly, the stigma and terror associated with the river and the rugged topography of land along its banks kept people away from it for long, leading to low levels of development along the river’s course. The curses thus acted as a blessing in disguise. Today, the Chambal remains one of India’s least polluted rivers, housing many species that have nearly become non-existent in many other water bodies where they were originally found.

To further protect this river’s precious wildlife, the National Chambal Sanctuary was established in 1979 by the Indian Government. It is a 5,400 km2 (2,100 sq mi) protected area shared by the three states through which the river flows. It is this sanctuary I was visiting that day. As I kept looking at the river and wondering about its thousands of years of history, the boat which was to take me and others close to the heart of this river was ready. The best time to visit the National Chambal Sanctuary is from November to March when the water levels are not as threateningly high as in the monsoons or extremely low as in the summer. Wildlife, including many species of migratory birds, can be spotted here during this time.

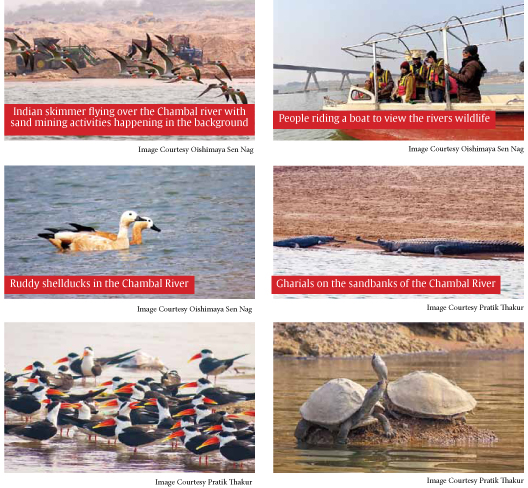

Gharials are the star attraction of this sanctuary. The pot-like protrusion on the snout of male gharials gives the species its name as “ghara” means “pot” in the local language. A member of the Order Crocodilia, gharials are found only in the Indian subcontinent’s freshwater systems, with the Chambal River being one of the last refuges of this critically endangered fish-eating reptilian. Nearly 80% of the gharial’s global population occurs in this region. The sanctuary also houses eight species of turtles, including another critically endangered species, the red-crowned roof turtle, which is endemic to South Asia. The river is also home to the delightful Ganges river dolphins, India’s National Aquatic Animal, and a large population of the ferocious mugger or marsh crocodiles, both being threatened species. But that is not all.

The National Chambal Sanctuary is also a birdwatcher’s paradise. At least 150 species of birds (both resident and migratory) have been reported at this site, including breeding populations of the endangered Indian skimmer and black-bellied terns.

As our boat journeyed along the river, I was awed by the rich wildlife viewing the river had to offer. It was brimming with life. Giant muggers were sunbathing peacefully beside the relatively docilelooking gharials on its islands and sandbanks. Flocks of Indian skimmers and black-bellied terns were flying gracefully over the river while the elegant ruddy shellducks graced its waters. Along the banks, you could see bar-headed geese prancing around and even Egyptian vultures in the distance. Look up, and the steep, jagged cliffs rising along the river also had life in its seemingly uninviting habitat. A small desert fox appeared out of nowhere only to disappear into its den on the cliff, while a monitor lizard could be seen leaving the water’s edge to swiftly climb up the cliff to have an adventure of its own.

However, not everything about the Chambal River is picture-perfect. While its bad reputation in the past definitely aided its wildlife to thrive by keeping the river safe from human disturbance, the stories have now been nearly forgotten, and the river is the site of many activities that threaten its ecosystem. Many hydroelectric, irrigation and water abstraction projects scar the river along its length, altering its natural flow. With water being diverted along the Chambal’s course, summers in the sanctuary lead to reducing the water levels in the river to threateningly low levels. A low-flowing river also makes it more accessible for people with their cattle and feral dogs crossing the river easily, trampling or destroying nests of birds and reptiles that lay their eggs on the sandy banks and islands of the river.

Rampant sand mining along its banks, including in the sanctuary itself, also devilishly deprive the river of its sand, destabilizing the ecosystem that takes millions of years to form.

The sand mining activities also deprive wildlife like gharials, crocodiles, and turtles of their nesting sites on the river’s sand banks. Despite protests over the years and many bravehearts losing their lives while trying to stop the illegal activities, the sand mining activities in the river continue. Overfishing and illegal fishing, poaching of wildlife, and increasing pollution levels also spell doom on this pristine river and its wildlife.

As my boat tour on this legendary river ended, I wondered about the fate of its many denizens I had just met. In India, where even the holy Ganges is regarded as extremely polluted, the Chambal has still managed to hold on to its purity and rich biodiversity. So, it will be a shame if the country allows one of its last pristine riverine ecosystems to lose its gifted biodiversity while investing massive funds to purify the other heavily polluted waters. Prevention is always better than cure. The Chambal needs to be kept safe from the scourges of human activities to ensure it continues to be a life-giving river, an extremely valuable resource, and a source of pride for India.